Human trafficking is present in every country in the world, which includes countries in the Middle East. Some of the best-known risk factors for increased trafficking include war, displacement, and poverty — all factors that have been consistently present in many Middle Eastern countries in recent decades.

Although exact definitions vary for what countries are included in the Middle East, this article will focus primarily on the Arabian Peninsula, including Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Yemen. Here is an overview of sex trafficking, labor trafficking, and forced marriage in these countries.

Prevalence of Human Trafficking in the Middle East

According to the most recent Global Slavery Index estimates, the Arab States have the highest prevalence of slavery per capita in the world. Just over 10 people per 1,000 in the Arab States are trapped in some form of labor trafficking, sex trafficking, or forced marriage. The Global Slavery Index identifies Saudi Arabia, in particular, as the fourth most prolific country in the world when it comes to the prevalence of modern-day slavery.

That equates to 1.7 million people being trafficked in this region on any given day in 2021. 52% of those individuals are in labor trafficking (including commercial sexual exploitation), and 48% are in forced marriages.

Although those numbers are based on the best data-collecting methods available to us, the truth is that there are still many unknowns. Frequent unrest and forced movement of people groups make the mechanics of exploitation opaque.

ECPAT International commonly evaluates violence against children and advocates for their rights. In a 2020 report on the Middle East and North Africa, they said, “The lack of attention and data on this topic has dire consequences for the 160 million children living in the region… Over 61 million children are living in countries affected by conflict, and the region as a whole has the highest concentration of humanitarian needs in the world.”

Some of the most recent country-by-country UN data on trafficking in the Middle East is nearly a decade old. This gap in accurate data can be attributed to a few different factors. Many organizations and authorities in this area do not have a comprehensive understanding of what trafficking is and thus are not able to accurately report it. In times of turmoil, information collection becomes more difficult and is unlikely to be prioritized. Depending on diplomatic relations between countries in the Middle East and other regions, there may also be no exchange of information happening.

The Kafala System and Human Trafficking

For most parts of the Middle East, the kafala system is trafficking’s linchpin. As defined by the Council on Foreign Relations, the kafala system is “a legal framework that has for decades defined the relationship between migrant workers and their employers in Jordan, Lebanon, and all Arab Gulf states but Iraq.”

Specifically, this legal framework allows a prospective employer to serve as a worker’s sponsor to bring them into the country. In theory, this would allow employers to source affordable labor easily. In return, they are expected to offer transport into the country, housing, and wages.

But in practice, this system gives employers almost total control over a migrant’s life. Even though, technically, migrant workers are legally supposed to be able to retain their documentation, employers often confiscate it.

This system has unintentionally perpetuated both labor and sex trafficking as companies and private citizens exploit loopholes. An in-depth investigation by the BBC proved exactly how costly these loopholes can be.

Foreign construction workers on the streets of Doha, Qatar.

Employers can transfer contracts under the kafala system, but the employee can’t transition their contract themself. This leads to many traffickers sponsoring large quantities of workers, getting them into the country with false job promises, and then auctioning their contracts off on social media or other apps designed for this purpose. Because technically, they’re “transferring contracts,” not “selling people,” their behavior passes as legal.

But the difference is purely semantic.

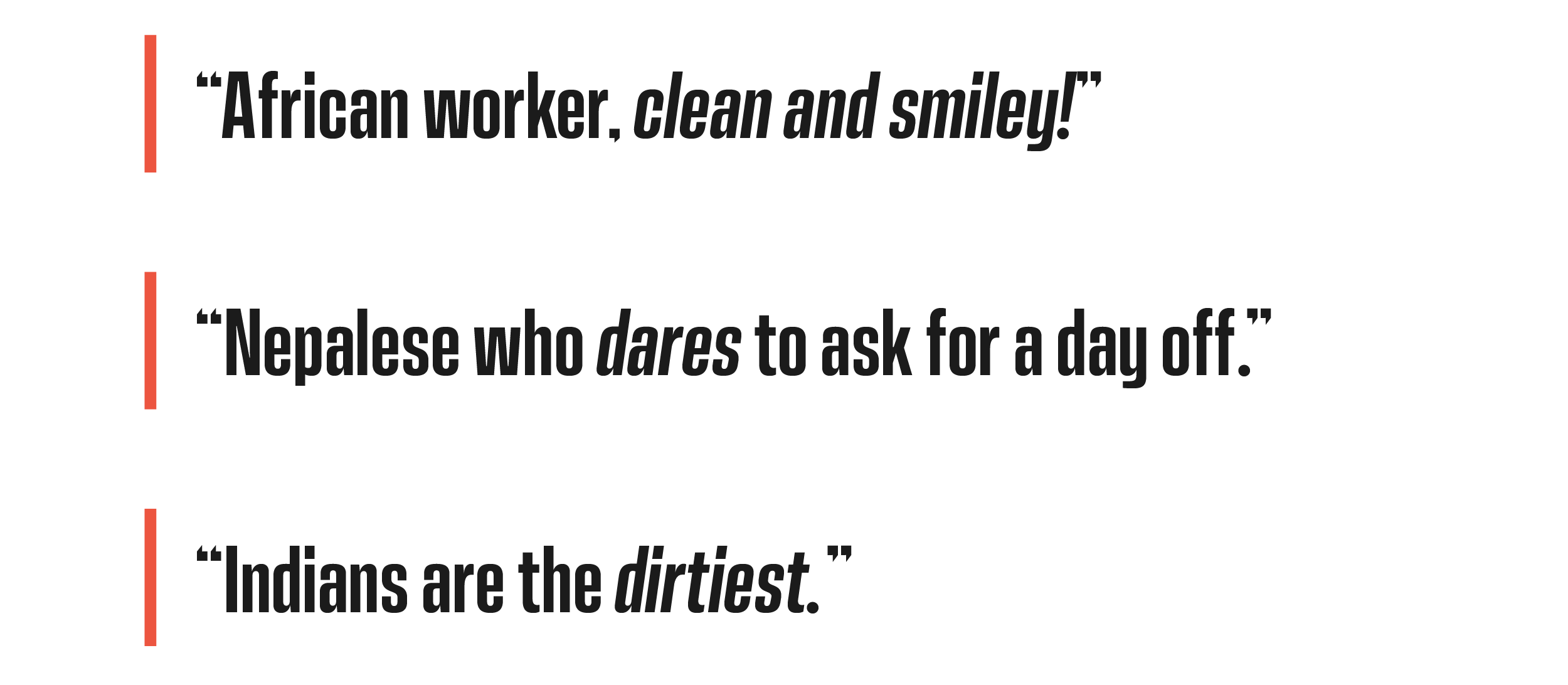

Here are direct quotes from sellers that BBC found:

Traffickers use specific hashtags on X (formerly known as Twitter), Facebook, and Instagram to hold their auctions. Sometimes, they’ll buy multiple people and then try to resell them at a higher price.

This is one of the most unambiguous forms of modern-day slavery in our world today.

Labor Trafficking in the Middle East

“In the context of the Middle East, the occurrence of forced labor and human trafficking is often linked to ineffective labor migration governance, which leaves migrant workers particularly vulnerable to exploitation,” states a pivotal report from the International Labor Organization. “Labour migration in the region has been influenced by trade, wars, tourism, and the discovery of oil. It is distinguished by its scale (in respect of both its absolute size and its exponential growth, at rates far beyond the global average).”

Conflicts leave individuals from neighboring Middle Eastern countries, Southeast Asia, and North Africa needing stable work. This makes them vulnerable to recruitment by employers who promise well-paying jobs. According to the ILO and the Global Slavery Index, these are common industries where individuals are in forced labor in the Middle East:

- Domestic work (housekeeping, nannying, cleaning)

- Construction

- Agriculture (including farming and animal herding)

- Manufacturing

- Seafaring (including fishing)

- Security services

Although most countries in this region have minimum age requirements for labor, they are rarely enforced. For example, Kuwait requires domestic laborers to be 21 or older. The BBC easily found a 16-year-old girl from Guinea trapped in an abusive work situation in a Kuwaiti home.

The United Arab Emirates provides a shocking case study. The 2023 Trafficking in Persons Report identified that almost 90% of the UAE’s residents are foreign workers. Although not all of these workers are being trafficked because of the kafala system, many of them are. The TIP report identifies the following labor abuses commonly happening in industries of service and manual labor:

- Withheld passports

- Lack of pay

- Limited movement

- Contract changes

- False job promises

- Inadequate food and shelter

These labor abuses affect people from a wide variety of backgrounds. For example, there has been an increasing influx of African women into the UAE and Saudi Arabia for domestic work. According to the ILO, in most countries throughout the Middle East, domestic workers are not considered to be protected by state labor laws.

The Exodus Road encountered a situation like this firsthand with Maria (not her real name), a woman from Kenya who was trafficked into Saudi Arabia. We were able to help Maria get home, supporting her as she was repatriated and accepted a role as a teacher at a nearby school. Unfortunately, thousands more young women are never connected to the right tools to help them get out.

Sex Trafficking in the Middle East

Sex trafficking is present in every country in the Middle East. As with other kinds of modern-day slavery, the unrest in the Middle East has made countless people more vulnerable — especially given that sexual violence caused by conflict disproportionately impacts women and kids, who are the most common victims of sex trafficking. A 2018 report from the Eban Center cites UN data in estimating that recent decades have seen a 600% increase in potential sex trafficking victims in the Middle East.

Often, sexual exploitation overlaps with other forms of trafficking. For example, a woman might travel to the UAE as a housekeeper under the kafala sponsorship system. When she arrives, the family that sponsored her to come confiscates her documentation and forces her to work for 14 hours every day. They also withhold her paycheck for 8 months, insisting she must pay back her travel and recruitment fees. To make matters worse, the family’s husband might decide she isn’t “earning her keep” through housework alone. He could begin to force her to sexually service clients to bring in more income.

A 2018 report from the Eban Center cites UN data in estimating that recent decades have seen a 600% increase in potential sex trafficking victims in the Middle East.

Even outside of sex trafficking, other kinds of sexual violence are common for the uncounted thousands of women in domestic servitude. Their isolated position makes it easy for employers to sexually assault women who have been labor trafficked.

As in other parts of the world, individuals who are sex trafficked in Middle Eastern countries usually arrive pursuing the promise of what seems like legitimate work. They may be driven by the desperation stemming from the challenges of poverty. A potentially lucrative job far away can seem like the answer to the costs of their family’s hunger or sickness.

Sometimes, they may even start doing the domestic work they came for — but then an employer might sell their contract to another owner, who exploits them for sex. People may also be outright abducted or else pursue the promise of an arranged marriage. Most of these pathways end with an individual being trafficked for sex out of a private home, small bars, or cafes.

In a chilling interview in 2012, a sex buyer in Kuwait said the following to ILO: “Any man who wants sex can call a number and contact a former domestic worker who is now working in a house. Each visit costs between 5 and 8 KWD ($18–30). The price depends on the nationality. It’s like a menu: 8 KWD to be with a woman from the Philippines, 5 KWD from Nepal, Bangladesh or India. The client will give the money to the man who runs the apartment.”

The complexities of escaping this degrading exploitation are intensified by the honor/shame culture in many countries in this region. A trafficker may force a woman into providing sexual services and then threaten to expose her to her family. Because of the extreme stigma around sex work and a lack of education about sex trafficking, this could legitimately result in the family killing the woman to restore their family honor.

In that same crucial ILO investigation, they spoke to a bar worker who had observed sex trafficking taking place.

“They are stuck because they can’t go back to their family; if they do, they will be killed,” the informant said.

Even if they don’t face threats to their life, the road out of sex trafficking is a dead end for most. With severe stigma around their past, most survivors are considered unhirable.

“I want to find a good job, but my only options are to sell drugs or become a police informant, neither of which I am prepared to do. There is no alternative,” one survivor said in desperation. “I did not eat anything today, and spent all my time looking for work. I want to commit suicide.”

Forced Marriage in the Middle East

Out of the 1.7 million people in modern-day slavery in the Middle East, nearly half (48%) are in forced marriages. That amounts to 816,000 people. Roughly 6 out of every 10 people in forced marriages are women, with the remaining 4 out of 10 being men and boys.

As with other forms of human trafficking, the data is limited and opaque. However, most sources agree that late-20th century progress in reducing child marriage has slowed in more recent decades. The COVID-19 pandemic and recent conflicts have further exacerbated stalled progress.

The UN agency UNFPA explains it this way: “Faced with insecurity, increased risks of sexual and gender-based violence and the breakdown of rule of law, families and parents may see child marriage as a coping mechanism to deal with increased economic hardship, to protect girls from sexual violence, or to protect the honor of the family in response to the disruption of social networks and routines.”

In some cases, the kafala system can also be used for coercive marriages. This leaves vulnerable spouses, even if they are fully of age, utterly legally defenseless if their partner exploits or controls them.

Forced marriage can often be the gateway into labor trafficking or sex trafficking, further proving the complexity and overlap that exists within spheres of exploitation. A young man who is forced to marry into a family might find himself coerced into providing construction help, without pay, for his father-in-law’s business. A teenage girl who is married at 16 may then be pressured to provide sexual services out of a room in her new husband’s home.

Out of the 1.7 million people in modern-day slavery in the Middle East, nearly half (48%) are in forced marriages.

How Conflict in the Middle East Impacts Human Trafficking

As is evident through each kind of modern-day slavery, conflict and political turbulence quickly multiply rates of trafficking. On top of those challenges, this region has been further imperiled by systemic social inequality, climate crisis, and economic unrest (most recently exacerbated by COVID-19). All of those factors lead to more migration, which leaves people at risk of being exploited.

Current Events Affecting Trafficking Rates

In 2024, the conflict in Gaza can be viewed as a case study for how political strife might impact trafficking. At the time of this article’s authoring, it’s too early for there to be any definitive data on how trafficking is occurring due to the fighting between Israel and Palestine. However, we know how this kind of instability has played out in the past.

According to the UN-operated reliefweb, “Women and children make up around 80% of the world’s displaced people due to conflict, and are more likely to be victims of trafficking.”

The UN has already published data about sexual violence against Israeli women that occurred during the October 7 attacks. While that violence does not constitute trafficking, it does prove that when fighting breaks out, the most vulnerable suffer the most.

Stop The Traffick has expertly assessed the region’s risk, summarizing, “The ongoing crisis in Palestine, resulting in a significant loss of civilian lives and displacement, has raised alarming concerns about the potential surge in human trafficking. Reports of alleged organ trafficking and theft highlight the urgency of the situation. As millions continue to be displaced, the risk of various forms of exploitation, including recruitment for sex and labour exploitation, is expected to rise.”

What Can Be Done?

One of the most crucial steps forward has to be better regulation of the migration process, and extending fundamental rights like minimum wage to foreign workers. The kafala system is deeply flawed, often providing what amounts to governmental sign-off on exploitive labor.

Every country in this region has officially signed the Palermo Protocol, a document from the United Nations that lays out basic expectations for how countries will respond to trafficking. However, despite lip service given to those standards, they are usually not implemented. The 2023 Trafficking in Persons Report shows how far many of these countries have to go.

Another essential action step for the global anti-trafficking community is collecting better data. This region has been neglected in studies that adequately and accurately assess the scale of the problem so that solutions can be proposed.

Finally, there is a grave need for survivor services in this region. Survivors of trafficking often voice that they were unable to leave because there was no one to help them on the other side. Services for those who have been trafficked for sex, in particular, are few and far between. Legal recourse for labor trafficking survivors is also inaccessible for most.

Resources for Reporting Human Trafficking

Although resources for fighting human trafficking are few in the Middle East, some do exist.

- UAE government’s official list of resources

- Directory of Human Trafficking Hotlines in every country

- List of services for survivors by country

If you’re interested in fighting trafficking in the Middle East, you’ve already taken the first step by reading this article and educating yourself. Next steps can include finding and donating to reliable organizations that fight trafficking in the region, including Free the Slaves and Caritas.

You can also continue supporting organizations that serve vulnerable communities in countries where those trafficked into the Middle East originate, such as The Exodus Road. We educate at-risk communities in source countries like Thailand and The Philippines.

A multi-pronged, collaborative approach is essential to combating human trafficking in the Middle East. But together, it is possible to disrupt the darkness of modern-day slavery in this region.